Read this ebook for free! No credit card needed, absolutely nothing to pay.

Words: 21409 in 5 pages

This is an ebook sharing website. You can read the uploaded ebooks for free here. No credit cards needed, nothing to pay. If you want to own a digital copy of the ebook, or want to read offline with your favorite ebook-reader, then you can choose to buy and download the ebook.

: Hogarth's Works with life and anecdotal descriptions of his pictures. Volume 3 (of 3) by Ireland John Nichols John - Hogarth William 1697-1764

STUDIES IN THE POETRY OF ITALY

PART I

THE DRAMA

"Whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own features, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure."

When Greece was at the height of her glory, and Greek literature was in its flower; when AEschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, all within two brilliant generations, were holding the polite world under the magic spell of their dramatic art, their rough and almost unknown Roman neighbors were just emerging from tradition into history. There the atmosphere was altogether one of struggle. The king-ruled Romans, long oppressed, had at last swept away that crumbling kingdom, and established upon its ruins the young republic; the unconsidered masses, still oppressed, were just heaving themselves up into legal recognition, and had already obtained their tribunes, and a little later the boon of a published law--the famous Law of the Twelve Tables, the first Roman code.

Three years before this, and in preparation for it, a committee of three Roman statesmen, the so-called triumvirs, had gone to Athens to study the laws of Solon. This visit was made in 454 B. C. AEschylus had died two years before; Sophocles had become famous, and Euripides had just brought out his first play. As those three Romans sat in the theater at Athens, beneath the open sky, surrounded by the cultured and pleasure-loving Greeks, as they listened to the impassioned lines of the popular favorite, unable to understand except for the actor's art--what a contrast was presented between these two nations which had as yet never crossed each other's paths, but which were destined to come together at last in mutual conquest. The grounds and prophecy of this conquest were even now present. The Roman triumvirs came to learn Greek law, and they learned it so well that they became lawgivers not alone for Greece but for all the world; the triumvirs felt that day the charm of Greek art, and this was but a premonition of that charm which fell more masterfully upon Rome in later years, and took her literature and all kindred arts completely captive.

Still from that day, for centuries to come, the Romans had sterner business than the cultivation of the arts of peace. They had themselves and Italy to conquer; they had a still unshaped state to establish; they had their ambitions, growing as their power increased, to gratify; they had jealous neighbors in Greece, Africa, and Gaul to curb. In such rough, troubled soil as this, literature could not take root and flourish. They were not, it is true, without the beginnings of native literature. Their religious worship inspired rude hymns to their gods; their generals, coming home, inscribed the records of their victory in rough Saturnian verse on commemorative tablets; there were ballads at banquets, and dirges at funerals. Also the natural mimicry of the Italian peasantry had no doubt for ages indulged itself in uncouth performances of a dramatic nature, which developed later into those mimes and farces, the forerunners of native Roman comedy and the old Medley-Satura. Yet in these centuries Rome knew no letters worthy of the name save the laws on which she built her state; no arts save the arts of war.

But in her course of Italian conquest, she had finally come into conflict with those Greek colonists who had long since been taking peaceful possession of Italy along the southeastern border. These Graeco-Roman struggles in Italy, which arose in consequence, culminated in the fall of Tarentum, B. C. 272; and with this victory the conquest of the Italian peninsula was complete.

This event meant much for the development of Italian literature; it meant new impulse and opportunity--the impulse of close and quickening contact with Greek thought, and the opportunity afforded by the internal calm consequent upon the completed subjugation of Italy. Joined with these two influences was a third which came with the end of the first Punic War, a generation afterward. Rome has now taken her first fateful step toward world empire; she has leaped across Sicily and set victorious foot in Africa; has successfully met her first great foreign enemy. The national pride and exaltation consequent upon this triumph gave favorable atmosphere and encouragement for those impulses which had already been stirred.

His first public work, to which we have referred above, was the production of a play; but whether tragedy or comedy we do not know. It was at any rate, without doubt, a translation into the crude, unpolished, and heavy Latin of his time, from some Greek original. His tragedies, of which only forty-one lines of fragments, representing nine plays, have come down to us, are all on Greek subjects, and are probably only translations or bald imitations of the Greek originals.

The example set by Andronicus was followed by four Romans of marked ability, whose life and work form a continuous chain of literary activity from Naevius, who was but a little younger than Andronicus, and who brought out his first play in 235 B. C.; through Ennius, who first established tragedy upon a firm foundation in Rome; through Pacuvius, the nephew of Ennius and his worthy successor, to the death of Accius in 94 B. C., who was the last and greatest of the old Roman tragedians.

While these tragedies were Greek in subject and form, it is not at all necessary to suppose that they were servile imitations or translations merely of the Greek originals. The Romans did undoubtedly impress their national spirit upon that which they borrowed, in tragedy just as in all things else. Indeed, the great genius of Rome consisted partly in this--her wonderful power to absorb and assimilate material from every nation with which she came in contact. Rome might borrow, but what she had borrowed she made her own completely, for better or for worse. The resulting differences between Greek literature and a Hellenized Roman literature would naturally be the differences between the Greek and Roman type of mind. Where the Greek was naturally religious and contemplative, the Roman was practical and didactic. He was grave and intense, fond of exalted ethical effects, appeals to national pride; and above all, insisted that nothing should offend that exaggerated sense of both personal and national dignity which characterized the Roman everywhere.

Free books android app tbrJar TBR JAR Read Free books online gutenberg

More posts by @FreeBooks

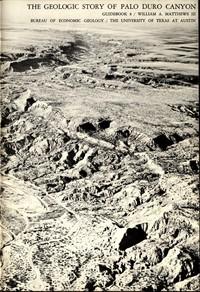

: The Geologic Story of Palo Duro Canyon by Matthews William Henry - Geology Texas Palo Duro State Park; Palo Duro State Park (Tex.)

: The Mentor: Rembrandt Vol. 4 Num. 20 Serial No. 120 December 1 1916 by Van Dyke John Charles Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Illustrator - Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn 1606-1669 The Mentor