Read this ebook for free! No credit card needed, absolutely nothing to pay.

Words: 28614 in 9 pages

This is an ebook sharing website. You can read the uploaded ebooks for free here. No credit cards needed, nothing to pay. If you want to own a digital copy of the ebook, or want to read offline with your favorite ebook-reader, then you can choose to buy and download the ebook.

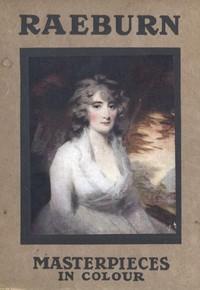

Plate

When in 1810, Henry Raeburn, then at the height of his powers, proposed to settle in London, Lawrence dissuaded him. It is unnecessary, as it would be unjust, to insinuate that the future President of the Royal Academy had ulterior and personal motives in urging him to rest content with his supremacy in the North. Raeburn was fifty-five at the time, and, after his undisputed reign at home, even his generous nature might have taken ill with the competition inseparable from such a venture. Lawrence's advice was wise in many ways, and Raeburn, secure in the admiration and constant patronage of his countrymen, lived his life to the end unvexed by the petty jealousy of inferior rivals. Nor was recognition confined to Scotland. Ultimately he was elected a member of the Royal Academy, an honour all the more valued because unsolicited. Yet, had the courtly Lawrence but known, acceptance of his advice kept a greater than himself from London, and, it may be, prevented the perpetuation and further development of that tradition of noble portraiture of which Raeburn, with personal modifications, was such a master. For long also it confined the Scottish painter's reputation to his own country. Forty years after his death, his art was so little known in England that the Redgraves, in their admirable history of English painting, relegated him to a chapter headed "The Contemporaries of Lawrence." Time brings its revenges, however, and of late years Raeburn has taken a place in the very front rank of British painters. And, if this recognition has been given tardily by English critics, the reason is to be found in want of acquaintance with his work. He had lived and painted solely in Scotland, and Scottish art, like foreign art, so long as it remains at home, has little interest for London, which, sure of its attractive power, sits arrogantly still till art is brought to it. But Raeburn's work possesses that inherent power, which, seen by comprehending eyes, compels admiration. The Raeburn exhibition held in Edinburgh in 1876 was quite local in its influence, but from time to time since then, at "The Old Masters" and elsewhere, admirable examples have been shown in London; and recent loan collections in Glasgow and Edinburgh, wherein his achievement was very fully illustrated, were seen by large and cosmopolitan audiences. And the better his work has become known, the more has it been appreciated. Collectors and galleries at home and abroad are now anxious to secure examples; dealers are as alert to buy as they are keen to sell; prices have risen steadily from the very modest sums of twenty years ago until fine pictures by him fetch as much as representative specimens of Reynolds and Gainsborough. Fashion has had much to do with this greatly enhanced reputation, but another, and more commendable cause of the appreciation, not of the commercial value but of the artistic merit of his work, lies in the fact that the qualities which dominate it are those now held in highest esteem by artists and lovers of art. Isolated though he was, Raeburn expressed himself in a manner and achieved pictorial results which make his achievement somewhat similar in kind to that of Velasquez and Hals.

Painted within a year or two of Raeburn's return from Italy, some critics have seen, or thought they saw, in this picture the influence of Michael Angelo. Be this as it may, the handling, lighting, and tone and disposition of the colour are eminently characteristic of much of the work done by Raeburn about 1790.

If, during the last century, Scotland has shown exceptional activity in the arts, especially in painting, and has produced a succession of artists whose work is marked by able craftsmanship and emotional and subjective qualities, which give it a distinctive place in modern painting, the more than two hundred years which lay between the Reformation and the advent of Raeburn seemed to hold little promise of artistic development. During the Middle Ages and the renaissance the internal condition of the country was too unsettled and its resources were too meagre to make art widely possible. Strong castles and beautiful churches were built here and there, but intermittent war on the borders and fear of invasion kept even the more settled central districts in a state of unrest. Moreover, the fierce barons were at constant feud amongst themselves, and not infrequently the more powerful amongst them were banded against the King. Of the first five Jameses only the last died, and that miserably, in his bed. The innate taste of the Stewarts, no doubt, created an atmosphere of culture in the Court, and this tendency was further strengthened by commercial relations with the Low Countries and political associations with France. Poetry and scholarship were encouraged, if poorly rewarded--one remembers Dunbar's unavailing poetical pleas for a benefice--and relics and old records show that even in those stirring times life was not without its refinements and tasteful accessories. Yet only in the Church or for her service was there the quietude necessary for art work of the higher kinds. Then came the Reformation severing the connection of art with religion and sowing distrust of art in any form.

Had the Union of the Crowns not taken place in 1603, it is possible that the art of painting might have developed much earlier than it did. No doubt that event brought healing to the long open sore caused and inflamed by kingly ambitions and national animosities, but it removed the Court to London, and with that some of the greatest nobles, while the change in the religion of the ruling house from Presbyterianism to Episcopacy, which followed, led to the Covenants and the religious persecution, and drove the iron of ascetism into the souls of those classes from whom artists mostly spring. Yet the logical rigidity of the Calvinistic spirit, while taking much of the joy out of life and opposing its manifestation in art, had certain compensating advantages. Disciplining the mind, quickening the reasoning powers, and cultivating that grasp of essentials which makes for success in almost any pursuit, and not least in art, it helped very largely to make the Scot what he is.

Only one of the three Raeburns in the National Gallery is an adequate example. This is the picture reproduced. It was painted in 1795, and, while very typical technically, possesses greater charm than most of the portraits of women executed by him at that comparatively early date.

Ramsay's activity as a painter coincided with a remarkable intellectual movement which, making itself felt in history, philosophy, science, and political economy, raised Scotland within a few years to a conspicuous intellectual place in Europe. A product of the reaction which followed the narrow and intense theological ideals which had dominated Scotland, it was closely associated with the reign of the Moderates, who, with their breadth of view, tolerance, and intellectual gifts had become the most influential party in the National Church. Offering an outlet for the human instincts and secular activities, it possessed special attraction for independent minds and induced boldness of speculation and original investigation of the phenomena of history and society. Intimate with the leaders in this movement, Ramsay, before he left Edinburgh for London, was active in the formation of the "Select Society," which in addition to its main object--the improvement of its members in reasoning and eloquence--sought to encourage the arts and sciences and to improve the material and social condition of the people. It was in this more genial atmosphere that Henry Raeburn was reared.

Born in 1756, Raeburn was not too late to paint many of the most gifted of the older generation. David Hume, who sat to Ramsay more than once, was dead before the new light rose above the horizon, and the appearance of Adam Smith does not seem to be recorded except in a Tassie medallion; but Black, the father of modern chemistry, and Hutton, the originator of modern geology, were amongst his early sitters; and fine works in a more mature manner have Principal Robertson, James Watt, the engineer, Adam Ferguson, the historian, Dugald Stewart, the philosopher, and others scarcely less interesting for subject. And of his own immediate contemporaries--the cycle of Walter Scott--he has left an almost complete gallery. Nor were his sitters less fortunate. If they brought fine heads to be painted, he painted them with wonderful insight grasp of character, and great pictorial power.

J. Michael Wright , at his best probably the finest native painter of the seventeenth century, went to England.

This is one of the finest of the many fine portraits by Raeburn in the Edinburgh Gallery. Its place in the artist's work is discussed on page 63.

The rapid expansion of Edinburgh provided new opportunities and helped to Raeburn's early success. When he was eight years old the building of the North Bridge, which was to connect the old city with the projected new town on the other side of the valley, was begun, and by the time he attained his majority many of the well-to-do had migrated. The new district meant bigger houses and larger rooms, and, with the increase in wealth which followed the commercial and agricultural development of the country of which the city was the capital, led to alterations in the habits and expansion of the ideals of its inhabitants. It was probably the opening for an artist offered by these altered circumstances which had brought Martin to Edinburgh, and certainly Raeburn was fortunate in that his emergence coincided with them. An attractive and clever lad devoting himself to art in a community increasing in wealth and expanding in ideas, and with a sympathetic master coming in contact with the upper classes, Raeburn could not fail to make acquaintances able and willing to help him. Amongst these was John Clerk, younger of Eldin, later a famous advocate, through whom the young artist got into touch with the Penicuik family which for several generations had been notable for its interest in the arts. And this would lead to other introductions.

Sir David Wilkie, Sir William Allan, and others were pupils of Graham.

Free books android app tbrJar TBR JAR Read Free books online gutenberg

More posts by @FreeBooks

: The Preacher of Cedar Mountain: A Tale of the Open Country by Seton Ernest Thompson Rowe Clarence H Clarence Herbert Illustrator - Western stories; Clergy Fiction; Great Plains Fiction