Read this ebook for free! No credit card needed, absolutely nothing to pay.

Words: 11970 in 4 pages

This is an ebook sharing website. You can read the uploaded ebooks for free here. No credit cards needed, nothing to pay. If you want to own a digital copy of the ebook, or want to read offline with your favorite ebook-reader, then you can choose to buy and download the ebook.

Plate

INTRODUCTION

Perhaps it would be hard to find more diverse opinions than those that are heard in the studio. Artists see life through the medium of many temperaments, they are notoriously intemperate in their enthusiasms. There are schools of painting to suit every conviction, and the work that one man would give his all to possess would not find hanging space upon the wall controlled by another. But before Velazquez even artists forget their controversies; he stands, like Bach and Beethoven in the world of music, respected even by those who do not understand. No controversy rages round him; he has marched unchallenged to the highest place in men's regard.

THE METHOD AND INFLUENCE OF VELAZQUEZ

When we come to analyse his work we find that its qualities are not of a sensational kind. Velazquez makes no appeal through the medium of brilliant pigment; his great contemporary Rubens used colour in far more striking fashion. Velazquez loved grey and silvery tints, and in the years of his maturity understood relative values perfectly. He knew, too, exactly how far he could go, and never made experiments in search of qualities that were not his. Although he had a certain quality of delicate imagination, he was a realist, and could not paint without a model; he never acquired a mannerism, or applied to one sitter the treatment that some artists seem to keep for types. Every figure he set upon canvas has its own individuality, and, while Velazquez, like other artists, had manners and methods that belong to fixed periods of his life, it is not easy to set down in cold print an analysis of the causes that make up his effects. He had no tricks; everything that he did was clear, simple, and withal inimitable. Hundreds of men have copied his pictures; none has been able to copy his method. With his death his influence upon art ceased. His genius lay buried in the grave with him, and did not suffer complete resurrection until the nineteenth century was turning towards its successor, though Raphael Mengs had done all he could to make his merits known a hundred years before. Even to-day, we may be said to be in the first stage of our enjoyment of the master's work. There are at least fifty good books upon the subject of Velazquez' life and art, written in three or four languages, and all published in the last half century; there must be many more to come, for every generation sees genius in the light of its own time.

So much for literature. In art the painter has influenced very many moderns. Manet, Courbet, Corot, Millet, Whistler, are among the men whose work shines in the light of the Prado, and the list might be prolonged indefinitely, for all earnest art workers go to Velazquez, confident that whatever their aims and ideals, he will confirm and strengthen what is best in them. They know, too, that they may return again and again, and that the rich stores of guidance and encouragement in the pursuit of ideals are as inexhaustible as the barrel of meal that did not waste, and the cruse of oil that did not fail, in the house of the widow of Zarephath.

THE PAINTER'S EARLY DAYS

VELAZQUEZ IN MADRID

Of the painter's work at court in those early days we hear a little from Pacheco, but the story of the times is more or less obscure. A clever portrait-painter was not a very interesting person in the eyes of a Spanish grandee. He was classed with the court buffoons and dwarfs who existed merely to amuse. Indeed, portraiture was not above suspicion in the eyes of some fanatics, who held that art existed to serve the Church, and should not seek secular employment. There are documents extant showing that Velazquez received eight pounds for three portraits, of which one is lost and the other two are in Spain. In 1625 the painter received a present of three hundred ducats, which was followed by a pension of the same value and a gift of free lodging, and, in 1627, by the appointment to the post of Gentleman Usher. There is no doubt but that the king was attached to his young court painter in a certain undemonstrative fashion. Pacheco tells us that Philip used to visit the artist's studio constantly, reaching it by way of the secret passages of which the palace was full.

The year 1628 marks an event of the first importance in the life of Velazquez, for Peter Paul Rubens came on a diplomatic mission to Madrid, charged by his government to pave the way to the conclusion of peace between England and Spain. Rubens was then about fifty years old. He stayed nine months in the Spanish capital, and, despite his diplomatic duties and the gout, found time to paint an extraordinary number of pictures, including five of Philip. He also copied the king's Titians. Velazquez was entrusted by Philip with the work of entertaining Rubens, and showing him the art treasures of Spain, and the friendship that grew up rapidly between the two artists was creditable to both, because Rubens, then at the zenith of his fame, recognised the amazing gifts of the young Spaniard, and Velazquez never allowed the brilliancy of the ambassador-artist to tempt him from the paths that he had chosen to follow. There are some who think that Rubens exerted a great influence upon his young friend's art, but we cannot pretend to trace it. Rubens may have widened his mind; he could not influence his hand or eye.

Shortly after Rubens left Madrid, Velazquez completed his picture "Los Borrachos," now in the Prado, and one of the acknowledged masterpieces of his first style, though the tone is dark, and some of the figures do not blend with their surroundings. In the late summer of the same year Velazquez left Spain for Italy, in the company of Don Ambrosio Spinola, who was going to take command of the Spanish forces. Soldier and artist parted at Milan, and the latter went to Venice, where he stayed with the Spanish ambassador and copied some of Tintoretto's pictures. Thence he went by way of Ferrara to Rome, the honoured guest of a relation of the Count of Olivarez, and he busied himself copying old pictures and painting new ones. Like many of the artists who go for the first time to Italy, he was influenced in some degree by Guido, who was then living. He painted his own portrait, which is to be seen in the Capitoline Museum, and went from Rome to Naples, returning to Madrid in the early part of 1651.

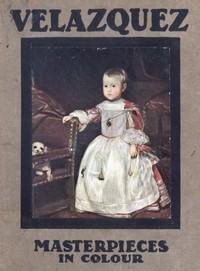

This is one of the Prado pictures of King Philip's eldest son by his first wife, the unfortunate little prince who died while he was yet a boy. When this picture was painted Don Balthasar Carlos was six years old.

Free books android app tbrJar TBR JAR Read Free books online gutenberg

More posts by @FreeBooks